One century ago this week a startling ad ran in the March 16, 1918 edition of the trade publication “Moving Picture World.” The bold two-page spread was run by Carl Laemmle (LEM-lee) of Universal Pictures.

In large type in the header and footer of the ad, Laemmle extended to his movie industry colleagues “An invitation to — close your studios and make all your pictures in Universal City.” It was a bold and extravagant gesture from a man who was no stranger to such bravado, and who indeed had been well served in his career thus far by such expressions of chutzpah.

Like many of the businessmen who achieved prominence in the early days of the emerging motion picture industry, Laemmle was a Jewish immigrant to the United States. He made his bones in the business world rising from bookkeeper to general manager at the Oshkosh, Wisconsin branch of the Continental Clothing firm, where he displayed a distinct knack for promotions. His ads, catalogs, and window displays were inventive and effective. He eventually left the company, driven by an ambition to own his own business rather than be a “salary slave,” but rather than follow his initial idea of opening a clothing store, he found himself drawn to the movie exhibition business. When his theater business began to thrive, he moved into the distribution arm of the industry, acquiring rights to movies from their production companies and then leasing prints to theaters.

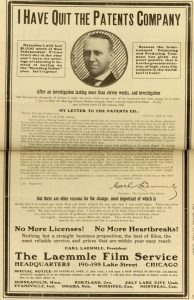

As you may gather from the photo above, Laemmle was a spirited and scrappy fellow, a feisty banty rooster who would never shrink from a fight just because the odds were stacked against him. It was a quality that served him well in his early days as an exhibitor and distributor, because his independent ways very quickly brought him into conflict with the emerging film industry’s dominant player. Thomas Edison and his business partners had formed a company that was unapologetically and straightforwardly designed for the purpose of monopolizing the movie business. Between them, the Edison group owned all of the essential patents covering the hardware needed to make and exhibit moving pictures, so they simply put all their patents into a common pool and froze everyone else out. This company’s origin and purpose were baked right into its name: the Motion Picture Patents Company. Like everyone else in the exhibition business, Laemmle had to pay a regular weekly $2.00 fee just to be a licensee of the Patents Company in addition to paying the rental fee for leasing the individual films. Frustrated by this, he decided to go rogue, canceling his Edison license and opting to import films from Europe — transactions that were beyond the reach of Edison’s legal team.

Here is where Laemmle’s proven talent for promotions came to the fore. He began taking out trade paper ads, beginning with, in effect, his personal declaration of independence from the Patents Company:

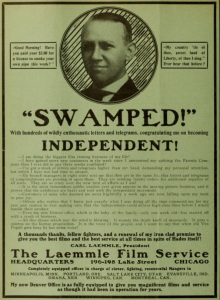

This was followed in the weeks to come by a series of ads proclaiming the success he was enjoying now that he was liberated from the oppressive yoke of Edison and his partners:

Declaring himself to be “swamped” with new business as an independent, he begins the ad with a sardonic reference to the Patents Company licensing fee: “Good morning! Have you paid your $2.00 for a license to smoke your own pipe this week?” He then closes his pitch with a rousing and melodramatic rallying cry: “A thousand thanks, fellow fighters, and a renewal of my iron clad promise to give you the best films and the best service at all times in spite of Hades itself!”

Some of his ads used cartoons to poke fun at the Patents Company, and, by extension, at those who unwisely continued to submit to their fees:

When foreign films became too difficult to obtain in the required quantities, the logical next step was to start making films himself. He took that step in 1909, opting to give up his theaters in favor of being just a producer and distributor.

As a promotional gimmick, he ran a contest to come up with a name for his new production company, offering a $25 prize for the best suggestion. The winning entry was the name “Independent Moving Pictures Company,” which undoubtedly appealed to Laemmle because it suggested an acronym, IMP, that reflected his personality. He even had a logo created using a cartoon image of an impish figure.

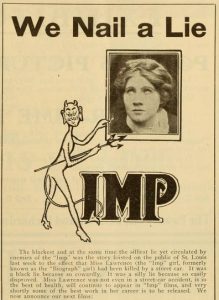

Now that he was a direct competitor with the Patents Company producers, Laemmle’s impish ways even extended to raiding their talent pool. Over at the Biograph Company (an Edison partner) a young actress named Florence Lawrence had become popular with audiences. Biograph, as a matter of company policy, did not publicize the names of its performers, so she was known to the public only as “the Biograph Girl.” Laemmle approached her with an offer of more money and successfully hired her away from Biograph.

But as a gifted promoter, he couldn’t let it go at that. To milk some publicity out of the acquisition of his new actress, Laemmle began circulating a story that the “Biograph Girl” had been killed in a street accident in St. Louis. Then he took out an ad condemning this scurrilous rumor (the one that he himself had planted):

“The blackest and at the same time the silliest lie yet circulated by enemies of the ‘Imp’ was the story foisted on the public of St. Louis last week to the effect that Miss Lawrence (the ‘Imp’ girl, formerly known as the ‘Biograph’ girl) had been killed by a street car” the ad indignantly affirmed. “Miss Lawrence was not even in a street car accident, is in the best of health, will continue to appear in ‘Imp’ films, and very shortly some of the best work in her career is to be released.”

Eventually the fortunes of Edison’s Patents Company declined, not least because they were found to be engaged in an illegal restraint of trade under the terms of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Laemmle and other independents had taken to referring to the Patents Company as a trust, and ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court agreed. Meanwhile, Laemmle had changed his company’s name to Universal Pictures and, along with a number of other independent companies that had defied Edison, had moved his operations to Southern California and become one of the founding fathers of Hollywood.

With the Patents Company effectively out of the way and Southern California proving to be exceptionally well suited to the production of movies, Laemmle began to dream big. He envisioned a production facility that would be more than a mere studio space. His grand concept was the creation of a self-contained city dedicated to the production of motion picture entertainment. In 1914 he expanded his property holdings in the San Fernando Valley, acquiring a 230 acre ranch which, over the next year, would be converted into “Universal City.” When completed, the property included, in addition to production stages, “a mayor to govern it and all the facilities and comforts of the best modern cities, including schools, churches, efficient police, firemen, and health board.” (“Moving Picture World,” March 20, 1915, vol. 23, no. 12, p. 1746.) This self-contained city even boasted its own zoo. After all, if your production schedule includes the occasional jungle movie it’s helpful to have the necessary exotic animals and their wranglers right there on the lot.

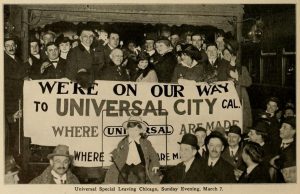

A grand opening was held on March 15, 1915, but Laemmle, ever the master of ballyhoo, stretched out the affair over several days by arranging a promotional train trip from New York to Los Angeles with plenty of press in tow. The trip included stops at Chicago, Kansas City, Denver, and the Grand Canyon before arriving in L.A. Here’s a picture of the train’s modest banner as it prepared to depart Chicago:

In order to leverage even more income from his investment, Laemmle also hit upon the idea of offering tours of Universal City to the general public. For 25 cents you could actually watch movies being made, and for an additional nickel the studio would provide a box lunch:

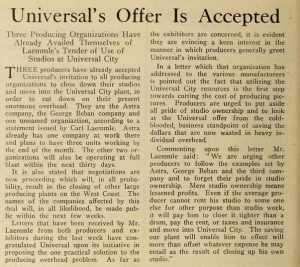

Then, in 1918, one century ago, Laemmle came up with yet another idea for using the property to generate revenue. As the ad shown above indicates, he extended an offer to other production companies to shut down their own studio shops and lease production facilities on the Universal City lot. It would have been absurd to believe, as the ad copy brazenly suggests, that the likes of William Fox, Mack Sennett, or Paramount’s Adolph Zukor would have closed down their own extensive facilities to come and work on the Universal lot. This was mere puffery on Laemmle’s part, not to be taken seriously. However, a couple of smaller companies did in fact take him up on the offer, as “Motion Picture News” reported in its March 23, 1918 edition:

The leasing of facilities to other companies did not, in the long run, prove to be a significant revenue stream for Universal, however. Moreover, when silent pictures gave way to talkies, it became necessary to discontinue public tours. With talking pictures came the imperative of “quiet on the set,” which meant that the inevitable noise from the peanut gallery as scenes were being shot could no longer be tolerated.

And yet the studio tour idea, as it turned out, was not dead; it was merely dormant. In 1936, Laemmle sold the studio and retired. Ownership subsequently passed through a number of hands, but it was in 1964, under MCA ownership, that the Universal Studios tour was reinstated. To this day you can still take a tour of this legendary back lot, but admission will set you back quite a bit more than two bits, and although the lunch options have expanded considerably the days of the nickel lunch are as defunct as the silent cinema.